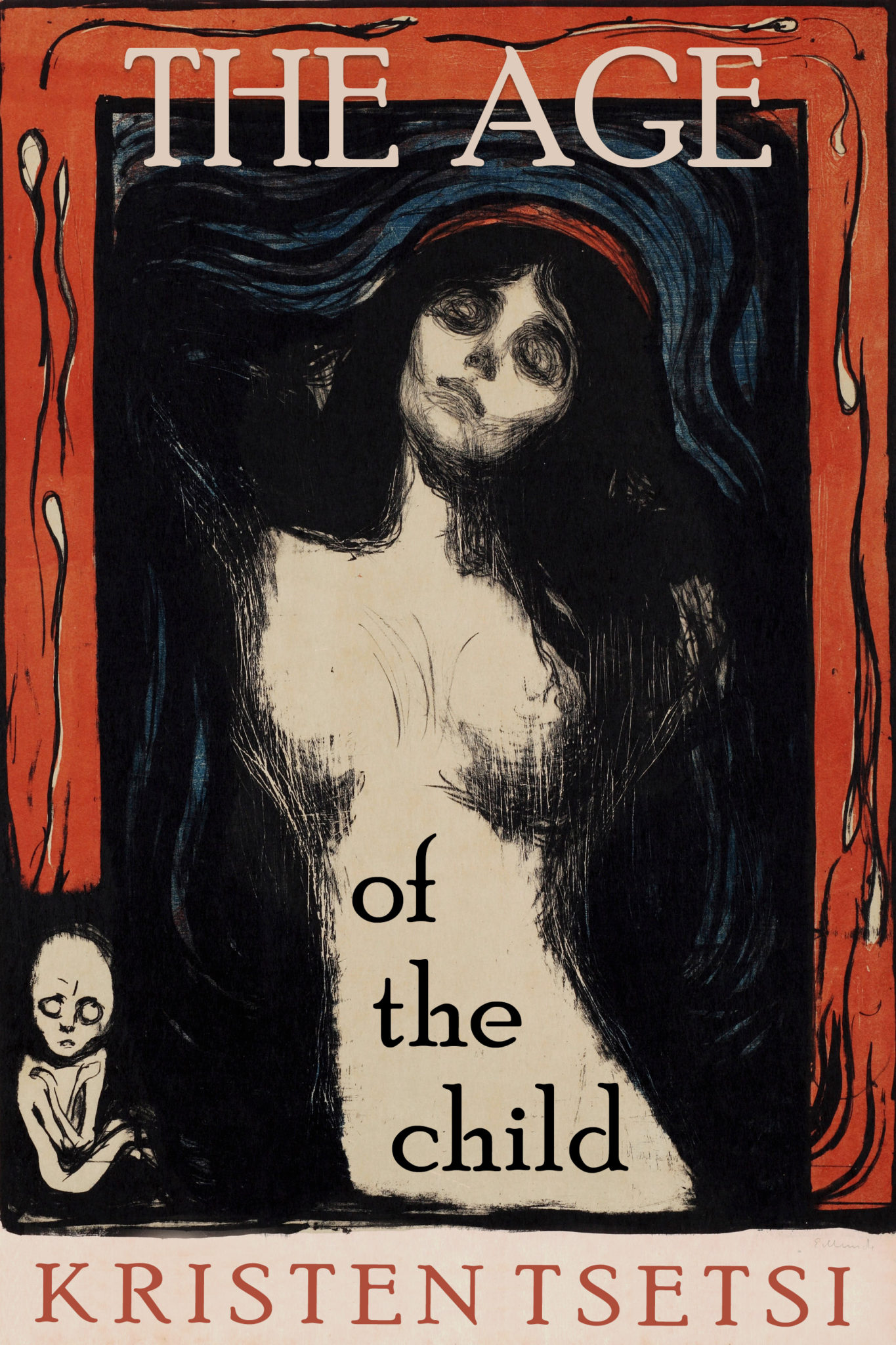

I think it’s natural that people will see a book cover heading this post and assume, “This chick’s trying to sell her book again.”

It’s a safe assumption, because I am. But for a reason. The whole thing was written for a reason. (Please indulge me.)

“I would never want a book’s autograph. I am a proud non-reader of books.” — Kanye West

–Wait. Wrong quote.

“…[F]iction is a valuable socializing influence.” — Scientific American

Maybe consider the book itself an extended blog post, and this short blog post an introduction to why I hope you’ll read the long one. Key words: abortion, pro-choice, pro-creation, child welfare.

The Age of the Child is so-named because, in the world inhabited by the characters in the novel, “think of the children” isn’t an empty demand made by hand-wringers who are really only interested a) in protecting their own children (from colorful liquor bottles, say), or b) in somehow suppressing someone else’s rights (“Two women in wedding dresses!? Think of the children!”).

Instead, it’s a world in which the government is actively, genuinely trying to protect the children. They begin by protecting the “unborn,” and they do this by criminalizing abortion (life sentences for the guilty), birth control (even suspected abortive aids, such as cinnamon and citrus fruits, are rationed), and some miscarriages.

This isn’t a world that’s hard to imagine. Women in Texas who live too far from an abortion provider, thanks to the closing of half of the enormous state’s clinics in 2016, are using the stomach ulcer medication misoprostol to induce a miscarriage. Then there’s Purvi Patel. And this list of five shocking injustices committed against pregnant women.

[Book note: I didn’t even know the first one on that list had actually taken place in real life when I created a similar, news-brief scenario in my book that features a teenage girl and her baby. In the case of the fictional character, the law chose to save her baby and let the girl die. The girl’s brother reasons that they chose to save the baby instead of his sister because his sister “was the older one.” So, you know, who cares about her?]

In The Age of the Child, the laws we (in real life) see slowly creeping over women’s reproductive rights have been implemented nationwide, and they don’t only affect women—they affect anyone, any sex or gender, found guilty of aiding in the prevention or termination of an unborn life. Again, this is an altruistic government — they don’t want to stomp on citizens’ rights; they want to protect and enforce the rights of all, including the right of potential citizens to become citizens.

The effect, however, is the same, and it’s the one the “think of the children” people today don’t really concern themselves with. As Emma Klein writes in this succinct delineation of the pro-creation movement in Becoming a Mother Reinforced Why I’m Pro-Choice, “The preciousness of babies is a constant refrain in anti-abortion rhetoric — but the focus is almost entirely on making sure they’re born. […] For the anti-abortion movement, the quality of the life they purport to hold sacred is a non-issue.”

It’s the quality of life issue that informed The Age of the Child.

I’m a childfree woman, and I’ve been writing and talking about being a childfree woman for close to a decade. When I started, it was from the perspective of someone who for years and through two marriages had felt pressured to be a mother. When you live in a society in which having children is a foregone conclusion, suddenly realizing you have no desire to be a parent can make you feel odd-ball enough, but add to it a husband who wants kids (and then a second husband who lies about being fine without them because he assumes not wanting them is a phase), and maybe you get a little indignant.

After a while, though, I started thinking about ALL of the people who are pressured to be parents, and all of the people who take for granted that, want it or not, they will produce children, and I started writing on their behalf. (Some sent me private messages to thank me. They’d actually had no idea they could choose not to have kids.)

And then, after learning through article research that five kids a day die in this country of neglect or abuse, I began thinking about all of the children who are born into inhospitable circumstances.

My focus shifted completely. Irreversibly.

An article I’d read years before, a particularly horrifying story about a little girl’s abuse, resurfaced in my memory. It was something I’d immediately regretted reading—sometimes, the details of a story are so terrible they find you at three in the morning—and I tried to forget it again. But I didn’t want to forget about the thousands and thousands of brand new innocent lives brought thoughtlessly and carelessly into the world and forced to live in misery at the hands of the same people they’re biologically predisposed to trust.

Whether in a TV interview (please ignore my hair and clothes) or in a (rejected by WaPo) response to an On Parenting article condescending to the childfree, the issue of “Do you feel pressured to conceive?” became secondary to what “Everyone — have kids!” says about how much we actually care about the quality of these children’s lives.

The Age of the Child addresses that concern, but it also addresses the notion of reproductive control—and flips it upside down with parent licensing. We’re all so accustomed to the same old pro-creation and pro-choice argument that the pro-creation activists probably can’t conceive of an alternate form of restriction on reproduction, one that denies parenthood to anyone who doesn’t pass an evaluation designed to determine their fitness as guardians.

Is it possible that when made to imagine being regulated, themselves, pro-creation activists will develop a broader understanding of how their stance impacts real people’s lives?

I hope so.

And I hope you’ll forgive my actively trying to draw your attention to a book I wrote. I genuinely consider it the same as sharing a link to an article, albeit a really really long (and fictional) one. But as John Waters writes in Role Models, “[D]on’t let me ever hear you say, ‘I can’t read fiction. I only have time for the truth.’ Fiction is the truth, fool! Ever hear of ‘literature’? That means fiction, too, stupid.’”

(I don’t think you’re stupid. That’s just part of the quote.)

Love,

Kristen

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called “scathing social commentary” and “a novel for right now.” She is also the author of the novels The Year of Dan Palace and Pretty Much True (studied in Dr. Owen W. Gilman, Jr.’s The Hell of War Comes Home: Imaginative Texts from the Conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq). Kristen’s interview series at JaneFriedman.com offers behind-the-scenes insights into all things writing and publishing.