Originally published in the Journal Inquirer November 6, 2012. This is the second article in a two-part series about traumatic brain injuries. The first in the series was Marriage and traumatic brain injuries.

By Kristen J. Tsetsi

If there’s anything that can be said with certainty about traumatic brain injuries, or TBIs, it’s that their different outcomes and issues make them nearly impossible to categorize.

If there’s anything that can be said with certainty about traumatic brain injuries, or TBIs, it’s that their different outcomes and issues make them nearly impossible to categorize.

There can be no list of uniform effects printed in a pamphlet titled “What to expect from your TBI,” because unlike diseases that have fairly predictable systems of attack, brain injuries–their severity and their lasting impact–vary according to the injury site, the healing ability of the individual brain, and the person who receives the injury. As the saying goes in TBI circles, “If you’ve seen one person with a brain injury, you’ve seen one person with a brain injury.”

The Centers for Disease control estimates 1.7 million Americans suffer a traumatic brain injury every year. Or as Julie Peters, certified brain injury specialist and executive director for the Brain Injury Alliance of Connecticut, puts it, six times more people will sustain a brain injury every year than will be diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, a spinal cord injury, HIV/AIDS, and breast cancer combined.

And according to the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, 30 percent of soldiers admitted to Walter Reed Army Medical Center since 2003 suffered traumatic brain injuries, called the “signature wound” of the wars in the Middle East.

A traumatic brain injury is a particular kind of acquired brain injury, one not present at birth and that is caused by any blow to the body that jars the brain. This includes concussions, which account for about 75 percent of traumatic brain injuries, the CDC says.

As brain injuries go, concussions are often considered “mild,” a word Peters discourages.

“There’s no way to determine from the severity of the injury what the long term consequences will be,” she says. “They may have very different outcomes and issues, so to categorize it as ‘mild’ is something we try to avoid.”

Concussions usually resolve themselves within a week or two, says Carrie Kramer, brain injury services director for the Brain Injury Alliance of Connecticut, but they can be of particular concern when they occur in young children whose brains are still growing.

“If they don’t get treatment for a concussive injury and they sustain a second injury, it can be devastating,” Kramer says, referring to what’s called “second impact syndrome,” a potentially fatal condition caused by a second injury to an adolescent brain that hasn’t properly healed. While rare, Kramer says, it can create “a cascade of problems in the brain and can lead to permanent disability or death.”

More severe TBIs, those that require acute care followed by rehabilitation, often have lasting effects, which has prompted the Brain Injury Association of America to promote the classification of TBI as a chronic disease. The association’s 2009 paper “Conceptualizing Brain Injury as a Chronic Disease” explains that traumatic brain injuries have long been viewed as the equivalent of a broken bone, an isolated injury that, once fixed, requires no further treatment and has no impact on other parts of the body.

“But,” Kramer says, “there is supporting evidence that those who suffer a significant brain injury experience sustained changes over a lifetime.”

The effects of severe traumatic brain injuries, and even some concussive brain injuries, fall along a vast spectrum, ranging from mild to severe and in any number of combinations. In many cases, a more severe brain injury will change who a person is, even if the change is subtle. There may be memory issues, mood swings, problems with concentration, and even changes in personality.

“My father became much more emotional, and he was never an emotional person,” says Kramer, whose father acquired a brain injury 15 years ago as a result of a stroke. “It was strange to experience him in a different way.”

She says the change in her father elicited remarkably different reactions from family members, depending on each person’s relationship with him. This is not unusual. Kramer, who has worked in the brain injury community for many years, explains that once the injured party has recovered from any physical effects of a trauma and there is no visible sign of a disability, sometimes “the person you knew is still the person you knew, but entirely different, and it’s really hard to adjust to that.”

It can be equally difficult for the person with the injury to adjust to their own changes. Kramer’s father, who before his stroke had always identified himself one way—an intellectual, a stockbroker, athletic, capable, community-focused—lost his identity for a time after the stroke.

“For a lot of people, there’s a mourning period,” says Peters. “It’s almost like a death, because you’re no longer the person you were. It can be very common for people to have to deal with that loss of who they were and then get okay with who they are now.”

Loved ones of those with brain injuries are encouraged, after mourning the loss, to get to know who the person has become post-injury and to recognize that they are “not less, just different,” Peters says.

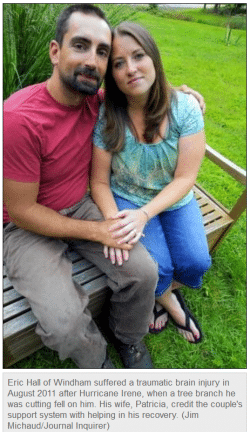

Patricia Hall, whose husband, Eric, sustained a brain injury last year when cutting down tree branches after Hurricane Irene, has been adjusting to changes in her husband that include mood swings and short term memory issues.

Patricia Hall, whose husband, Eric, sustained a brain injury last year when cutting down tree branches after Hurricane Irene, has been adjusting to changes in her husband that include mood swings and short term memory issues.

To help her deal with the changes, she has seen a therapist and regularly attends support groups with her husband. Additionally, she says, they have a wonderful support system that she credits with aiding in her husband’s recovery.

Outcomes are always better when there is a good support system, says Kramer.

What’s needed will be unique to the individual with the injury and may involve anything from arranging transportation to helping navigate daily life.

Peters urges brain injury survivors and/or their loved ones to contact the Brain Injury Alliance of Connecticut, which provides connections to resources, brain injury (and injury prevention) training and education, and support for the injured and their loved ones. This includes how to communicate with someone with a brain injury.

Hall says that when people first learned of her husband’s TBI, they would look at him differently, as if he might suddenly drool or do something else unexpected. For that reason, he was reluctant to let people know about his injury.

Kramer advises treating, and speaking to, someone with a TBI the same way anyone else would be treated or spoken to. If they need help, she says, they’ll ask, “and if they can’t ask, you’ll find a way to ask.”

Finally, the injured and their friends and family are advised to hold onto hope.

“Hope does make a difference,” Kramer says. “The families and survivors need to feel they’re moving toward something. It makes a difference in recovery.”

And there’s plenty of reason to be hopeful. It once was believed that little to no healing would occur beyond the first year following a brain injury, but new research indicates the brain remains capable of making new connections and pathways, and experiences positive growth, well past that first year, Peters says.

However, a brain injury cannot be reversed. The only cure, Kramer says, is prevention. Peters and Kramer say risk of traumatic brain injury can be significantly reduced by wearing helmets that are properly fitted and activity-appropriate, and by eliminating distractions while driving. They also recommend seeking medical attention for any injury that could potentially have impacted the brain so that appropriate healing can take place.

“It doesn’t matter what your ethnicity is or how old you are,” says Kramer. “A traumatic brain injury can impact anyone at any time.”

For support or for more information, call the Brain Injury Alliance of Connecticut at 860-219-0291, or contact the help line at 800-278-8242 Mon. – Thurs., 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., and Fri. 8:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Or visit:

Brain injury specialist Julie Peters says one or more of the following signs occurring within several hours of a jolt to the body may point to a concussion:

– A headache that gets worse

– Fatigue

– Confusion or disorientation

– Slurred speech

– Nausea or vomiting

– Feeling “foggy”

– No memory of being hit, or of the moments immediately preceding or following the hit

– Dizziness

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called “scathing social commentary” and “a novel for right now.” She is also the author of the novels The Year of Dan Palace and Pretty Much True (studied in Dr. Owen W. Gilman, Jr.’s The Hell of War Comes Home: Imaginative Texts from the Conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq). Kristen’s interview series at JaneFriedman.com offers behind-the-scenes insights into all things writing and publishing.