Originally published in the Journal Inquirer Monday, June 9, 2014

By Kristen J. Tsetsi

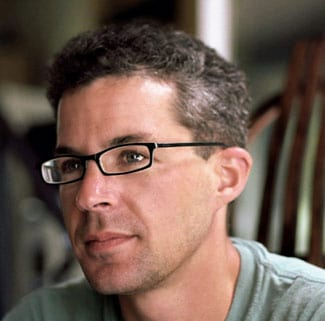

There are certain freedoms granted to young males. Author Alex Myers remembers that as a child his brother was allowed to wear pants to church and could go outside to play afterward. Myers, born a biological female and given the name Alice, had to wear a dress and girl’s shoes that weren’t supposed to get dirty.

“At a very young age, I never understood why I was being told I couldn’t do things that were fine for my brother,” Myers said. “Boys can get messy and it’s cute, but girls aren’t supposed to do that.”

“At a very young age, I never understood why I was being told I couldn’t do things that were fine for my brother,” Myers said. “Boys can get messy and it’s cute, but girls aren’t supposed to do that.”

The subject of gender identity is more complicated than “I want to do what they get to do,” but the arbitrary rules the sexes are expected to follow even when the biological sex matches the person’s own gender identity somewhat mirror the rules many transgender people have difficulty accepting. For example, which parts of the country to avoid for safety reasons, and whether someone born with certain physical characteristics is “allowed” to identify as someone other than what those characteristics have traditionally dictated.

It was his personal experience with gender identity that helped Myers approach the complexity of Deborah Sampson Gannett, the focus of his debut historical fiction novel “Revolutionary” (Simon & Schuster).

Gannett, of whom Myers is a distant descendant, is famous for having disguised herself as a man in order to join the Continental Army and fight in the Revolutionary War. And although Myers is unsure whether Gannett struggled with gender identity, he does believe she experienced comparable restrictions and discrimination as a woman living in the 1700s.

Gannett, of whom Myers is a distant descendant, is famous for having disguised herself as a man in order to join the Continental Army and fight in the Revolutionary War. And although Myers is unsure whether Gannett struggled with gender identity, he does believe she experienced comparable restrictions and discrimination as a woman living in the 1700s.

“Women weren’t allowed to travel alone when she was alive,” he said. And in the colonial era, he added, a female child could essentially be sold as a servant. “I don’t know that she wanted to be a man, but I know she wanted to be independent and free, and the only way to do that was to be a man.”

In “Revolutionary,” the 22-year-old character Deborah Samson has suffered years of indentured servitude only to find herself spending soul-dulling hours behind a weaving loom. To escape that life, she adopts the appearance of a male by binding her chest, cutting her hair, and stealing a neighbor’s clothes to wear. She gives herself the name Robert Shurtliff, and as Robert, she enlists in the Continental Army. As one author endorsement describes Samson’s journey, “In following her true nature — who she is at heart — Deborah creates for herself a duplicitous life fraught with personal risk.”

Myers logged hundreds of hours of research while writing “Revolutionary,” in part to learn everything he could about the woman he used to hear about as a child from his amateur genealogist grandmother.

Among his findings were her signature as “Robert Shurtliff” on a retirement log and a letter Paul Revere wrote on her behalf when she applied for a pension. He also learned that Gannett didn’t have the “amazing, exciting” life he’d imagined for her while listening to his grandmother’s stories.

“I had no idea how poor she was,” Myers said. “I had no sense that, when she was four, her father abandoned the family, so her mom was left raising seven children in rural Massachusetts.”

Myers also came across some surprises while digging around to find the small details that work together to bring history to life. For instance, because the Samson family in the story was so poor, Myers knew money and what it could buy would be something he would have to put into perspective. He imagined that Samson as Shurtliff while bunking with male soldiers would probably change clothes when it was dark and no one could see, which led to thoughts about lighting and candles — and how much candles cost.

It turns out a full day’s labor would buy just thirty minutes of candlelight.

He was also interested to learn during the course of his research that hundreds of women would follow their husbands or brothers to battle, trailing along behind them and doing the laundry and the cooking. Precisely the kind of role he imagines Gannett was not content to play.

In “Revolutionary,” Deborah Samson’s reaction to a friend’s recommendation that she marry is not at all ambiguous: “Marriage? For you, perhaps. […] There is a world out there, Jennie, beyond weaving, beyond housework…” She describes her first day dressed as a man, which is also incidentally her first (failed) enlistment attempt, to Jennie thus: “I felt…like I could go anywhere. No one to chide me, to herd me back to my proper sphere. I might have done anything I felt like and no one would have said a word against me.”

The desire to go anywhere, to do anything, without having “a word said” against it is a feeling familiar to Myers, who was told “Don’t be stupid” by his friends when he said he wanted to work out west. “You’re trans,” they said. “If people find out, you’ll get in trouble. Leave middle America alone.”

This is not unlike the treatment the character Deborah Samson receives when she’s discovered to have attempted to enlist. “The statutes of the Commonwealth forbid a woman to dress as a man,” a lawyer informs her. Such statutes may not officially be in place today, but similar disapproval is often openly communicated.

And for Myers, who said he wants only that he and everyone else may freely go where they want to go, be who they want to be, and love who they want to love, the courage it must have taken for the real Deborah Sampson Gannett to risk the consequences, to have gone as far as removing a musket ball from her own wound to avoid being discovered, is “beyond remarkable.”

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called “scathing social commentary” and “a novel for right now.” She is also the author of the novels The Year of Dan Palace and Pretty Much True (studied in Dr. Owen W. Gilman, Jr.’s The Hell of War Comes Home: Imaginative Texts from the Conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq). Kristen’s interview series at JaneFriedman.com offers behind-the-scenes insights into all things writing and publishing.