Don’t know much about poetry.

I studied it in high school and college the way most people do in high school and college, but I never developed the same feel for it that I did for fiction, whether reading or writing. I can make a rhyme, choose a good word here and there, and technically craft what might be called a poem, but that’s not the same thing as being a poet.

K. C. Hanson, once in the Marine Corps and now an instructor of composition at Minnesota State Community and Technical College and North Dakota State University, is a poet (as well as a fiction writer). A few lines down from here in the Q&A, I ask him why he chose poetry instead of fiction for his latest project (poetry is probably the only thing that sells worse than literary fiction), but he also discusses “Why Poetry?” more generally at more length here. For a taste:

I write each morning because of a kid on a blue bicycle, his orange flag waving, who one afternoon rode through a set of mud-puddles over and over again yelling “shit,” and “fuck,” “shit-fuck,” or some combination of these and others as he laughed and laughed, giddy with delight. I watched him. I don’t think he knew what any of those words meant. He seemed to only know two things: they were powerful, so powerful, in fact, the people in power told him he could never say them, and they sounded cool, all hard and bouncy and rhythmic, like their sound could get at the sense of it, create meaning, which is a rare and powerful emotional event.

But, back to me for a second … As someone moderately interested in poetry but lacking a passion for it, I tend not to buy it. (“Tend not to” is a lie. I just don’t. I don’t buy poetry.)

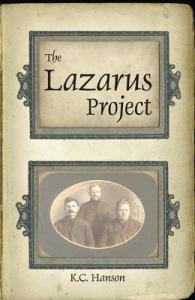

However, I did buy Hanson’s book of poetry – and it’s short, just 50 pages – after reading a description of The Lazarus Project (North Star Press, $12.95) that appeared in my Facebook feed:

However, I did buy Hanson’s book of poetry – and it’s short, just 50 pages – after reading a description of The Lazarus Project (North Star Press, $12.95) that appeared in my Facebook feed:

It started as just this picture, which my wife found in an antique store in Big Timber Montana. We just couldn’t leave that little girl sitting there, so we bought the picture and brought it home. It ended up on our refrigerator, and over the next year people kept asking about these two: how we knew them, who they were, how we were related. I eventually wrote a poem about it, then poems for many others, trying to give them a voice — trying in my own feeble way to wake the dead.

I immediately bought, read, and enjoyed The Lazarus Project (“enjoyed” is putting it mildly). When I finished, I contacted Hanson for an interview because, as much as I liked the book, I was pretty sure I wouldn’t rush out to buy another poetry collection – unless I knew Hanson had written it. (I think he’d understand. “When I showed up at college, fresh out of the Marines and wanting to become a writer, I was sure I hated poetry. I said as much, loudly,” Hanson said to me at one point. If he could hate poetry once, I can certainly get away with having lukewarm feelings toward it.)

Knowing that many people feel the same way I do about poetry, I needed to know what would inspire someone – him – to put so much work into something so grossly under-appreciated.

I also wanted to know more about the collection, as well as his time in the Marines (“Marine poet” doesn’t automatically compute, thanks to film stereotypes).

.

.

.

INTERVIEW WITH K. C. HANSON

Q: How would you characterize your high school self?

A: I was a D student. I didn’t do homework, but I kept track of points, so I knew how many questions I had to get right in order to pass. To make things interesting, I would only answer that many questions on the test. I remember skipping chemistry class and just going to the library. Mr. Krack would come in to the library as well, when the students were working on something, and we would visit, about guns and ballistics, mostly. He never mentioned that I was missing his class.

Outside of school, I was a farm kid. I grew up inside a tractor, back and forth, back and forth, around and around and around — hours, days, weeks, years. If only there was such a thing as a PhD in swather operation, I’d have it made. Corner office at the institute of swather management, easy, with Agatha, my swather, bronzed on the manicured campus lawn. It wasn’t all work, though. We shot stuff, hunted, fished…

Why did you join the Marines?

Why the Marine Corps? I never even considered any other service. Join the Marines, or don’t join at all. I suppose I had read more about the pacific theater in WWII than the European. Anyway, I wasn’t going anywhere. No plans. No work other than the farm. And I certainly didn’t want to go to another school. Wanna join the Marines? Why not. I know that should have been a question. It wasn’t.

I did write while I was in, and read. The Marine Corps was less anti-reading, as far as I can tell, than high school. Marines read all the time. Hell, they have an official reading list (I thought about contacting General Pace when he was chairman of the joint chiefs, to see if I could help update that). And there were lots of artists. Art is okay. Art is cool. Of course they don’t call it that. (“Hey, whachoo drawin, numbnuts?” — “fuckin’ piture. Why?”)

When I ran into the guy who was in the hole next to mine when the war ended, Kittle, twenty years later, one of the first things he asked about was my writing. I need to send him a copy.

I was in for six years — grunt, not pogue. It sucked world class ass, but I wouldn’t trade a minute.

What is your feeling about the literary landscape and poetry’s place in it?

Wow.

Critics have been arguing about what is or is not poetry, and just who gets to determine that, for centuries. What is or is not literature, that’s a little newer, but just as messed up.

Let me take a different run at this.

I wrote a poem, years ago, called “Spring Wind.” In it, the leaves are rolling back and forth in the street, swirling around, running into the curbs. Think of the street as the literary landscape. The leaves are all the things we write. Words, if you will. Sometimes they pool up, and you can play in them. That’s a novel. Poetry, to me, is those words scampering, swirling, playing buffalo. Sort of pointless, really, except sometimes those buffalo lift into flight.

Spring Wind

(printed here with the author’spermission)

Last fall’s dead dry leaves

chase each other across the asphalt

twirling and whirling

and scampering about,

then thundering in tremendous herds

across the street.

You’d almost swear they were playing

buffalo,

until they lift as great flocks

to flight.

What’s it like trying to sell/publish poetry? Was it a challenge to find a publisher for The Lazarus Project?

It’s like mailing babies.

Early on, I submitted a lot of stuff. I probably had a dozen submissions out at a time. It was a bloodbath. I wallpapered a bathroom with rejection letters. No lie. Some magazines were kind enough to send two at a time. You have to do something with them.

Now I concentrate on the writing. That’s what matters in the long run, anyway.

Finding North Star was a bit of a fluke. I started visiting with a bookseller, and asked him if he was interested in a book that was almost certain to lose money. He laughed and gave me his card. I mailed it to him. Two years later, Anne called.

In that whole time — most of it was written by 2005 — only two poems from the collection were published elsewhere, and neither with photos. Everything I sent out with a photo was rejected.

Like I said: mailing babies.

Your collection contains 34 pictures. When did you write the first poem (“Loving Father, Beautiful Child”), the one about the photograph your wife found in the store , and what made you seek out more photos?

2003, I think. I know we bought the picture in the spring of 2002. 9-11 was still fresh, anyway. And it hung on the fridge for about a year before I wrote on it. I really didn’t think much of it, at the time. Then I started seeing them. They’re everywhere, you know — old pictures — boxes and albums full of forgotten people, forgotten lives.

How did the stories behind the pictures form? What was the process like?

Every one was a different journey, sort of like meeting a person, you know? Some people you feel like you know right away; others, you have to buy them coffee — stay a while.

I need more than that.

They were all so different. Very difficult to answer. I’ll try to walk you through one, “I Played Pa,” and see if that helps.

One morning, over coffee and sitting down to write, sifting through the box of pictures, I run into this picture of three kids. It isn’t the first time I’ve seen this picture. I bought it, somewhere along the way. So it must have said something, I suppose. But in this case I have no idea how it got there. It just suddenly is. So I set it on the desk and look at it and drink some coffee. I scribble a little. I remember drawing a bit, turning a scribble into a mountainlike thing. I write a few words– five, maybe. I don’t recall what words, exactly, though one was pa. That was the first hour.

The second hour I spent trying to decide if the kid in the middle is a boy or a girl.

I hauled that picture around with me, then, though that didn’t happen with many others. It’s a 50/50 split, by the way, if you ask people. I kind of like that. I like that everyone is so absolutely sure even more.

The next day I concentrated on the gun. It’s a Steven’s Favorite. A falling-block-action single-shot .22. I have one, so I got it out of the cabinet and cleaned it (it needed it). That and drinking coffee pretty much consumed the second day of writing. No words.

The third day starts, coffee in hand, with a rifle on my desk, on top of a legal pad with 5 words and a scribble that looks like a hill on it, and a picture of three kids, playing dress-up. One is ornery, one distracted, and one, the leader, well, she’s a dreamer, right? Or she’s playing a dreamer, Pa. And then I had the first line: I played Pa, the dreamer, though the gun/ was real.

Ten words in three days. I told you I write slow.

Which is your favorite picture in the collection, and why? And is that the one you would also say had the strongest impact on you?

Wilhelmina Louise Griswold. Cute kid. So happy. She looks just like one of my little sisters. The bowl, the stirring, the swirl. I must have tried that photo a dozen times. On the desk. Back in the box. On the desk. Box. What, exactly, does she have to do with the Statue of Liberty? I don’t know, but that’s where it kept going.

What I do know is she came in a box off the internet, and she had a brother named George. Everyone called him Bud, or Buddy. He joined the Marine Corps and made it to Sergeant, so I know I have close to a decade of their history. There were no other pictures of her. This is the only one.

You also write fiction. Why poems instead of short stories for the pictures?

In a way, these are fiction. They are made-up truths. The poetic form, however, that choice was a matter of size and shape. Pictures are boxy things. So are sonnets. Pictures are rhythms of light; poems, sound. They fit together so nicely on the page. They marry. The Project needed that.

I felt, when reading The Lazarus Project, like it had a stronger impact on me when I went from poem to poem, one after the other, than it would have had I picked up the book, read a poem, and then put it down. Is there a way you imagine the collection being read for the best effect?

I had two ideas in mind.

First, that each poem would become attached to a photo, that together they would become not two pieces of art, but one, standing alone together. A true marriage — neither going anywhere alone.

Second, that the collection become a work of art. That bound together, chatting, their many voices would sing in chorus.

I want you to read it both ways.

Do you still pick up old pictures now that the project is complete?

I haven’t bought any, but I can’t seem to pass by without looking through them, either. Their prices have gone up. I’ve noticed that. And dealers are sorting them. That wasn’t happening when I started. I suppose I shifted the market a bit. I have several hundred I haven’t written on, so I sometimes wonder if it is complete.

How would you describe this collection? What does it say, or what do you hope people come away with after reading it?

Describing the collection has been a struggle.

Yesterday, I approached Greg Danz at Zandbroz (Zandbroz Variety, Fargo, ND) about doing a reading. He asked what it was I had written, so I said, “a collection of sonnets based on antique photos.”

His response, like all responses, included “a collection of what?”

When I handed him a copy, however, he immediately said, “Oh. Raising the dead, are we?”

I think my book falls short of that (perhaps necessarily so) for the people in the pictures, but I hope readers walk away with a different context for their own lives, an appreciation for the frailty and grandeur of their hopes and dreams. That’s a kind of resurrection as well.

Thank you, K.C.

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called “scathing social commentary” and “a novel for right now.” She is also the author of the novels The Year of Dan Palace and Pretty Much True (studied in Dr. Owen W. Gilman, Jr.’s The Hell of War Comes Home: Imaginative Texts from the Conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq). Kristen’s interview series at JaneFriedman.com offers behind-the-scenes insights into all things writing and publishing.