In the interest of recording history, I recently interviewed a friend who deployed to Iraq several years ago. I chose him because he’s honest and thoughtful, and because of his experience. He’s been on two combat deployments to Iraq and six non-combat deployments to various countries around the world.

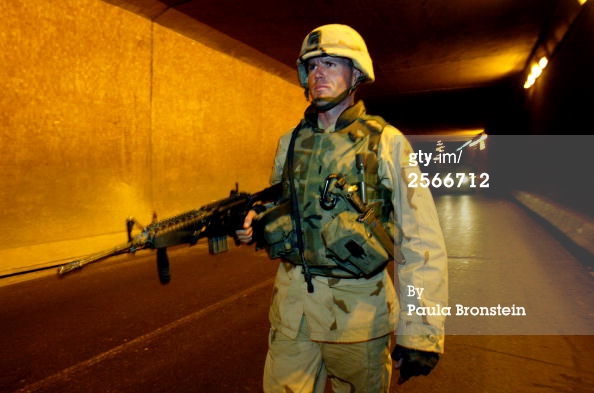

L. Andrew Arlint, who joined the Army in 1993 shortly after high school graduation, is currently a Federal Law Enforcement Officer with Immigration and Customs Enforcement and a Major in the Civil Affairs branch in the US Army Reserve assigned to Special Operations Command – Europe.

He’s also a Getty image.

We exchanged the following questions and answers via email. Some of the original questions and some answers have been edited here only for length.

__________________

.

Q: When were you in Iraq as a member of the infantry, and what was your rank at the time?

A: I was an Infantry platoon leader in Iraq from May 2003 to July 2004 at the rank of First Lieutenant.

Q: What was your mission?

A: The informal mission assigned to my Troop by our Brigade Commander after first arriving in Baghdad at nearly midnight on Memorial Day in 2003 was to “find bad guys, and kill ’em.” We immediately departed the base to execute our mission.

The formal mission of our Troop was twofold: one was to be the Personal Security Detachment (PSD) of the Brigade Commander and the Brigade Sergeant Major. The other was to conduct route clearance, offensive operations, reconnaissance, and combat patrols throughout the Brigade sector, which was all of Northeast Baghdad and some of the outlying areas.

Q: It’s tempting for many of us at home to imagine the deployed life of a member of the infantry as one filled with nearly constant conflict, danger, gunfire, and door-kicking. (In Iraq or Afghanistan, anyway – many of us have seen, in movies, depictions of the hours and hours of tense waiting soldiers experienced in Vietnam). Is that what it was like for you?

A: Each day was different as we cycled between PSD duties and our combat patrol/route clearance duties.

The operational tempo was intense. We did a lot of door-kicking and we were often exposed to gunfire. We would normally be “out of the wire” for at least 14 hours a day patrolling the streets of Baghdad.

At times, we would be required to conduct reconnaissance on a suspect’s residence wherein we would be required to literally crawl into some nearby bushes and watch the building for 24 hours or more, having been inserted in the dead of night.

Other times we would drive far out into the countryside, occupy an abandoned home, and conduct multi-dimensional reconnaissance around the area. A multi-dimensional reconnaissance is when information is gathered simultaneously about routes, people, structures, and enemy activity, as opposed to just watching a house, or driving a route.

Q: How much did you think about the politics of the war, or the reasons for it, while you were there? That is, were they either a source of pride and commitment or (if you disagreed with the politics and reasons) conflict, or did you not really entertain those thoughts?

A: I thought about the politics and reasons for deploying to Iraq often. I was in disagreement about going to Iraq, since we were already involved in Afghanistan, but I had faith in my leadership that they knew things I didn’t know. I realized a few months after arriving in Iraq that the leadership had not been forthright with the American people. Rather than feeling downtrodden by that realization, I shifted my satisfaction in our mission to the fact that we had, in deed, liberated a people from a tyrant. That was an accomplishment.

A: I thought about the politics and reasons for deploying to Iraq often. I was in disagreement about going to Iraq, since we were already involved in Afghanistan, but I had faith in my leadership that they knew things I didn’t know. I realized a few months after arriving in Iraq that the leadership had not been forthright with the American people. Rather than feeling downtrodden by that realization, I shifted my satisfaction in our mission to the fact that we had, in deed, liberated a people from a tyrant. That was an accomplishment.

Q: If asked for your best memory of your time in Iraq, what immediately comes to mind?

A: My best memory in Iraq was watching the sunrise over the sleepy city of Baghdad from one of the freeway overpasses as we began our patrol. There was not a single vehicle on the road, not a single report of an AK-47 rifle being shot, not a single sign of war being fought. It was the quiet before the storm.

Q: What is your worst memory of being in Iraq?

A: My worst memory in Iraq occurred at about 10:30 on Christmas Eve in 2003 when an IED hit Command Sergeant Major Cooke’s vehicle, killing him almost instantly, in the Adhamiyah District in Baghdad. He remained conscious long enough to collapse into the arms of one of my NCO’s arms. Staring up at the sky, meaningless sounds spilling from his mangled face, he drifted into death.

That was not the worst event I experienced in Iraq, but it was most certainly the worst memory. CSM Cooke and I had a unique bond: our mothers lived in the town of Molalla, Oregon. They were only a couple of houses apart. He and I would often entertain the idea of meeting in Oregon and enjoying some beers together after the war. The morning of his death, he and I had talked about how neat it would be if we introduced our mothers so that they could share in the experience of having their sons at war. Perhaps it would help them to cope. They never met.

That was not the worst event I experienced in Iraq, but it was most certainly the worst memory. CSM Cooke and I had a unique bond: our mothers lived in the town of Molalla, Oregon. They were only a couple of houses apart. He and I would often entertain the idea of meeting in Oregon and enjoying some beers together after the war. The morning of his death, he and I had talked about how neat it would be if we introduced our mothers so that they could share in the experience of having their sons at war. Perhaps it would help them to cope. They never met.

The morning after his death, Christmas morning, my base came under mortar attack. With the sound of mortars impacting directly above my room in the monument, I raised my hands toward the ceiling in disgusted protest and gave two middle fingers to the sky. Fuck you!

Q: It seems at times like there’s an uncomfortable level of hero worship when it comes to American service members. Granted, they’re definitely due the appreciation they receive for voluntarily choosing a profession that could be dangerous and that takes them away from home for long periods, but it’s gotten to the point where they – all of them, anyone in any military uniform – are treated as if they’re beyond reproach. They’re praised for their strength and heroics while simultaneously being handled with kid gloves (“Don’t joke about soldiers,” “Don’t say anything bad about a soldier”). There’s a certain pedestal effect. What is your reaction to, or opinion of, that kind of treatment of members of the military?

A: I, personally, appreciate reverent gratitude most. A simple thank you and a handshake, or a hug, are all I desire as appreciation for my service.

I believe that the “Fox News” level of extreme gratitude is unwarranted, in many cases, and can have negative effects.

If a service member, who is by all accounts mediocre during their time in service, receives the praise of a hero, then when that service member leaves the military for the civilian world, where people normally do not receive praise for just wearing a uniform, that service member is at risk of having unrealistic expectations. They might find it difficult to achieve fulfillment in standard living. I call it the “Honey Boo Boo disorder,” which is when a person is undeservedly popularized and praised to an extreme, resulting in an inability to adapt to standard living, which could lead to real psychological and behavioral disorders. (That statement is not based on any scientific information but simply my casual observations.)

I think it’s important to recognize service members (DoD, DoS, etc.) for their service to this great nation, but it should be done with reverence and humility, not flamboyance and opulence.

Q: How closely did you engage with the Iraqi civilian population, and how would you describe the community and the people?

A: I conducted over 300 patrols in the first six months I was in Iraq, which made my contact with the Iraqi people a very common occurrence. Many of my encounters with them were from a distance, with my body armor donned and my rifle slung across my front. I was either yelling at drivers who had congested a downtown intersection with vehicles going every direction, or I was looking down my sights at potential assailants.

A: I conducted over 300 patrols in the first six months I was in Iraq, which made my contact with the Iraqi people a very common occurrence. Many of my encounters with them were from a distance, with my body armor donned and my rifle slung across my front. I was either yelling at drivers who had congested a downtown intersection with vehicles going every direction, or I was looking down my sights at potential assailants.

Periodically, I was able to have personal discussions with Iraqi workers and interpreters in our Forward Operating Base (FOB). They were more centered around why America is good and Saddam was bad. That’s what I liked to hear. I was interested in very little else, which is unfortunate because I didn’t allow myself to understand the community and the people. Until I left the chaos of Baghdad.

When conducting multi-dimensional reconnaissance in the outlying areas, I would often be invited by Iraqi farmers and villagers to drink tea with them. We would inevitably talk about the war, and a surprising number of them had no idea we had invaded the country. (That always made for interesting discussion.)

Sitting in their shaded tents was somewhat comforting. My soldiers and I would remove our body armor and place our weapons at our sides, out of sight. It was there that I found the Iraqi people to be kind and inviting. I discovered that they were not dissimilar from rural Americans in that they cared little about international, or even national, matters as long as they were left alone. Unfortunately for them, their apathy did them no good. They had become unwilling participants in a conflict beyond their understanding.

Q: What was your understanding, based on what you heard from Iraqis themselves (if anything), of why the Iraqis you engaged with in battle were fighting Americans?

A: The reasons for fighting the American occupation evolved during my combat experience. When I first arrived in Baghdad, I was fighting criminals. The entire city was wrought with lawlessness and many people had acquired weapons, which were previously band during Saddam’s reign. Attacks were rarely coordinated and often only involved a small number of people.

There was a lull in the turmoil. The criminals were being killed or arrested, and the people were beginning to return to pre-conflict activities. The reduction in firefights didn’t last long, however.

Leaders started to emerge and rally groups of people. Suddenly, attacks became organized and involved more people. An ideology began to emerge in some of the communities that deemed our occupation unlawful and a direct affront to Islam. A new threat emerged against us, an insurgent threat.

The enemy took on many faces. Some fought us because they saw us as an oppressive force on their home soil. Some fought us with a desire to fill the governmental power vacuum that was created when we overthrew the government. Some fought us on the principle that our mere existence as a country was against Islam. Some (Sudanese, Somalis, and Chechen) came from across the world just to fight Americans and improve their tactics, techniques, and procedures to take back to wars in their homelands. There were so many overlapping reasons people chose to fight us that it created a very difficult situation when attempting to stabilize the country and establish an effective government.

Q: Can you describe one of your more tense/intense moments in Iraq?

A: There a number of intense moments, but one of my most intense moments occurred in July of 2003 at about 05:30.

I had acquired access to a special MCI phone with unlimited calling to the United States, so I used that to call my wife at the time, Kelly, every morning from 05:00 to 06:00. One morning, I was in the bed of a large transport truck, a 5-Ton, talking to Kelly. The truck was parked atop the smooth, flat marble surface that made up the roof of my unit’s quarters in the belly of an Iraqi monument memorializing the dead from the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s.

As Kelly and I prattled, the conversation was suddenly interrupted by a large blast. Kelly asked what the sounds was. I told her it was a mortar, and that it landed pretty far away. It was nothing. We continued to talk for a few seconds when another mortar impacted next to the truck I was sitting in, peppering the canvas with shrapnel. I yelled, “SHIT!”, hung up the phone, and leaped out of the bed of the truck. I hit the ground and rolled. Before I knew it, I was back on my feet running toward the stairs descending into the monument.

I could hear another mortar inbound. Instantaneously, it impacted just a few yards from me to my right. The blast and heat collided with me, but I continued to run toward the stairs. Another mortar hit to my front-left, closer than the last one, but the blast was redirected by a low wall bordering the entrance to the stairs. I could hear another mortar falling just as I reached the stairs. In a blink, I was at the bottom and around a corner. A few more mortars impacted above, but I was safe. I looked down at my body to inspect my limbs and torso. I was sure I had been hit by shrapnel with how close the mortars landed to me, but nothing burned. I felt no pain. Miraculously, I didn’t have a scratch on me. I hollered, “WHOOOO!” It was as though I’d just made the winning touchdown at a Sunday night football game.

That was a pretty intense moment.

Q: Young civilians will sometimes meet a soldier who’s come home after being at war and say, “So, did you kill anybody?” Maybe they think it’s exciting, or maybe they simply can’t imagine such a thing and are curious. But as someone who has known you now for over 10 years, and who sees you as happy, fun-loving, kind, and perpetually smiling, I’d like to ask (if I may) what it was like for you after the first battle that required you to shoot someone, what it felt like to know, that first time, that you had killed a person. I ask with no expectations about your reaction, and without judgment.

A: Since you asked me this question not a day has passed that I haven’t thought about the answer. At first, I didn’t want to answer it. Then, I would decide to write about the events in detail. I went between these two options for as long as it’s taken me to respond. I thought about how what I said might be used, how it might be viewed.

Ultimately, I’ve resolved to say this: I didn’t feel anything, except relief that what I had done stopped the bullets from coming at me and my soldiers. I never had to get up close to the bodies, which I’m sure helped me to process my actions. In fact, even now, I mentally keep my distance from the bodies by not ever thinking about the events in stark detail.

Q: What was being home like those first few weeks after returning from Iraq?

A: When I first returned from Iraq, I felt strange. Similar to the rolling sensation one gets standing on solid ground after spending a long period on a small boat in the ocean, I could still “feel” Iraq’s dangers all around me. A bag of debris on the roadside would cause me to gently swerve into the next lane to increase my distance from the bag as if it were an emplaced IED.

Two nights after my return, a large festival in the adjacent town launched a barrage of fireworks that had me leaping from a sound sleep and scrambling around the room looking for my weapon and body armor. Even after I realized what was creating the noise, I found it difficult to ease my nerves enough to go back to sleep. I watched the sun rise that morning.

Q: Sebastian Junger gave a TED talk about what returned service members miss about war. Did you miss anything about it after you came home?

A: I did miss the war. Iraq in 2003 and 2004 was chaotic and we, the US military, were the dominant force. It was a civilly primitive environment with very little “red tape”. The rules were relatively simple and the environment galvanized my relationship with those around me in a common theme that few outsiders could really understand.

Returning from that lawless environment to civil society, where you couldn’t run a car off the road if you were trying to get somewhere in a hurry and you couldn’t point your weapon at a person encroaching on your personal space, was difficult and frustrating.

Also, every picayune complaint people had seemed to grate on me. There was no way to discuss the experience with people who truly understood.

I’m sure it’s the same for people who are exposed to events and activities that the majority of people either can’t talk about, or don’t talk about. It took me about one month to fully adjust back to normal Western living.

Thank you, Andy, for your willingness to answer these questions, some of which I later learned were more difficult for you to answer than others. – Kris

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called “scathing social commentary” and “a novel for right now.” She is also the author of the novels The Year of Dan Palace and Pretty Much True (studied in Dr. Owen W. Gilman, Jr.’s The Hell of War Comes Home: Imaginative Texts from the Conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq). Kristen’s interview series at JaneFriedman.com offers behind-the-scenes insights into all things writing and publishing.