What does a successful writer have to worry about? How does someone with nearly constant creativity-on-the-brain manage a romantic relationship? Are male and female writers really that different? Kris Saknussemm answers these questions and more in this installment of 5 On.

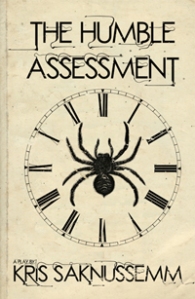

Kris Saknussemm is the author of eleven books, including the Philip K. Dick Award nominated Zanesville, Private Midnight, which a Starred Review in Publisher’s Weekly described as “David Lynch meets James Ellroy,” and Sea Monkeys, a memoir. His play The Humble Assessment was the highlighted main stage work at the 2013 Las Vegas Fringe Festival and is now in production as an independent feature film. Amongst his many recognitions are First Prize in the Boston Review’s Short Story Contest, First Prize in the Missouri Review’s 10 Minute Play Competition, and Australia’s Mary Gilmore Award. He has been a fellow at the MacDowell Colony and was the 2012 Gallagher Fellow at the Black Mountain Institute of UNLV, where he currently teaches. His major work in progress relates to the time he spent earlier in his life in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Kris Saknussemm is the author of eleven books, including the Philip K. Dick Award nominated Zanesville, Private Midnight, which a Starred Review in Publisher’s Weekly described as “David Lynch meets James Ellroy,” and Sea Monkeys, a memoir. His play The Humble Assessment was the highlighted main stage work at the 2013 Las Vegas Fringe Festival and is now in production as an independent feature film. Amongst his many recognitions are First Prize in the Boston Review’s Short Story Contest, First Prize in the Missouri Review’s 10 Minute Play Competition, and Australia’s Mary Gilmore Award. He has been a fellow at the MacDowell Colony and was the 2012 Gallagher Fellow at the Black Mountain Institute of UNLV, where he currently teaches. His major work in progress relates to the time he spent earlier in his life in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

.

5 ON WRITING

.

Q: You’ve been writing for much of your life: plays, short fiction, novels. You’ve also been successful. What kind of writing-related pressure do you struggle with at this point, if any?

KS: Money, audience, credence, hope—does anything I care about matter to others? All the original questions still apply. But some things have changed. I sold my first genuine story at 16 for $150 and my second for $750. Seemed like a lot of money then. I had a personal interview with Tennessee Williams, by virtue of winning a national playwriting contest at age 17. I drove a white 1970 Dodge Charger at the time. Into the great wide open. Everything was wide open. Is it the same today? Or is it time for what Graham Greene called a “crepuscular reexamination” for us all? Writing poetry was actually once a reasonable way to pull chicks. At my first big reading when I was in college, the guy who’d taught me how to skin a woodchuck showed up on a nitro-powered ice racing motorcycle with studded tires. Whatever happened to him?

You say in an interview at Bare Knuckle Poet that writing, or maybe being a writer, cost you a marriage. If I may ask, was it the time spent writing, the stress over searching for a publisher, or something else that challenged the relationship, and have you since learned how to create better balance?

You say in an interview at Bare Knuckle Poet that writing, or maybe being a writer, cost you a marriage. If I may ask, was it the time spent writing, the stress over searching for a publisher, or something else that challenged the relationship, and have you since learned how to create better balance?

Honestly, I think the relationship was stressed of its own accord, but 12 years isn’t a bad go for any couple. I’ve since learned how to share what I’m thinking and writing about better. And I’ve learned how to find other manifestations of my work that will connect with my friends and intimates, who are not directly associated with the writing in ways they can dig. My key intimate partner in Australia, after my divorce, isn’t a great reader. But she has a very fine eye for the best of my paintings, most of which are connected to my writing in some way. I reached out to my musician friends the same way. So, I’ve grown in how I listen to and appreciate others.

But as to spousal/life partnership connections—it’s hard. I think there is an inherent selfishness in a life in art that can’t be dismissed. I don’t have any issues with speaking to or performing in front of a lot of people. Alone in a room or a car with someone? Different story, different guy.

I guess we all search for that close quarter partner who can understand who we’ve been since the get-go. Not that we don’t make mistakes or need correction—but we all need a baseline of acceptance of who we are, so that we can be more for them. Would it work better if the other person were an artist too? I don’t know.

Why do you write what you write?

I often misheard things as a child, and developed elaborate mythologies around those mistakes. That’s fundamentally what my idea of art is. I started writing when I was seven—because I did the math and realized I was soon going to run out of Hardy Boys books. So, I created The Benton Boys! Part of the same logic remains operational. But what I’m writing now has changed a great deal from what I thought I was writing when I started. I’m now openly addressing, and I hope, figuratively assaulting, the question of what it means to grow up, to “have grown up,” even if I’ve lacked the cultural ceremonies to validate that (most of us today, in what I call the Cargo West, are in the same canoe).

I think it’s very important that male writers revisit the question of what it means to be a man—and it’s essential to the health and well being of society as a whole that we encourage this interrogation. Females need their own review and recalibration for the same reasons. But basically, I write from two standpoints—my dreams, which I ritually record—and peculiar fault line moments that I’ve been party to in “real life.” I triangulate these through research and extrapolation. Dreams and seemingly random misunderstandings in parking lots have always been the inspiration. Regrets…something I heard someone say one rainy night far away from home.

Do you make an effort to fit into a brand mold (even one of your own creation), or do you write what you want to write the way you want to write it?

Unless you are very pure genre writer, a brand mold is something you won’t have much control over, anyway. Write the best writing that comes forth from your innermost being—the most individual—what no one else can do. I think of it as being on the porch with my heroes. If it comes my turn, what am I going to say? I had a student once, a very emotionally challenged individual, who died young. He told a “duck walks into a bar” story I still think is one of the best things I’ve ever heard.

You may choose only one of your books to represent you and your writing in the distant future. What do you choose, and why?

REVEREND AMERICA is currently my best and most accessible book. PRIVATE MIDNIGHT is the published work I’m most proud of, because it hurt the most. It did very well in France and Italy—and Bulgaria. But always the answer should be one’s latest work in progress, which in my case, begins at 6,000 feet over the Bismarck Sea, with an eight foot-long tranquilized crocodile regaining consciousness in a twin-engine plane that’s being pursued by the Indonesian military. Why? Because it takes some doing to get into that kind of situation. I always wanted to know people like that—and suddenly I’d become one. Growing up, my friends and I had this expression, “Is it serious yet?” I’ve rediscovered that joy and fear.

.

5 ON PUBLISHING

.

There was a kerfuffle in 2012 over male vs. female authors and the treatment they receive when it comes to awards and recognition, even book covers publishers assign to each. (Pink and pretty for girls, artistic and more complex for boys.)

You happened to say that same year, in an interview in Spontaneous Combustion, “If I had to get specific about writers I continually come back to, Cervantes, Swift, Sterne, Melville, Kafka, Faulkner, Miller, Dick and Burroughs come to mind—but there are many, many others (and I have large sections of the Sherlock Holmes canon committed to memory). My favorite female authors are Djuna Barnes, Clarice Lispector and Katherine Anne Porter.”

Why the “female authors” distinction? Would you say that in the world of published writing there is a difference between male and female writing and how each is, or should be, received?

I once worked with blind people, and they explained some of the differences between males and females in ways that liberated and permanently influenced my thinking. If we’re honest, there’s often as big a difference in male and female writing as there is in males and females who physically walk into a room—their scent, or the timbre of their voices. The question is, can we appreciate those differences and expand our own lives around them?

We are much more open to these things in music and the visual arts. Writing/literature seems parochial and perspective-fixed to me, sadly. But we should all be free to admire the artists who speak to us. I like the late Kathy Acker more than my female writer friends do. We had drinks once and yelled the whole time. It was fabulous. Many people dote on Frieda Kahlo. I respect that. I prefer Helen Frankenthaler. There’s a Facebook cult of Nina Simone. I’m more spoken to by Sarah Vaughan. I minored in Native American Studies in college and got to meet Leslie Marmon Silko. She was a beautiful woman when she came to read. That wasn’t why I wrote a major essay about her work. I think my point about the female writer distinction is that men of my age have been pummeled about not engaging with female artists (of all kinds), and I have. I just don’t toe an easy party line.

In the end, I’m weary of the relentless emphasis on gender that is one of the defining elements of our time. But I think there is unquestionable evidence to indicate that writing today (and therefore reading) is female led. The pendulum has swung. Some people just don’t want to acknowledge it.

You’ve been published by one of the Big Five (Random House), smaller presses like Soft Skull, and you’ve self-published. How would you characterize the pursuit of a (your) desired publisher?

I have a lot of respect for Algonquin Books. I like McSweeney’s, but they are something of a closed shop. Of the majors, I still admire Viking, Little Brown and FSG, although much of what they publish is a bit conservative for my tastes. I hear good things about The Free Press and Soho, although I’ve never had anything to do with them myself. The publisher I most admire overall is an Australian company, Text Publishing in Melbourne. They have a relationship with Canongate in the UK and Grove in the US. Ideally, I seek to have three channels open: an edgy New York imprint, one of the strong small presses (such as Lazy Fascist in Portland, who are doing some very exciting things), and then my own imprint for special projects that don’t fall into a clear commercial frame, or which have a strong multimedia component.

I have a lot of respect for Algonquin Books. I like McSweeney’s, but they are something of a closed shop. Of the majors, I still admire Viking, Little Brown and FSG, although much of what they publish is a bit conservative for my tastes. I hear good things about The Free Press and Soho, although I’ve never had anything to do with them myself. The publisher I most admire overall is an Australian company, Text Publishing in Melbourne. They have a relationship with Canongate in the UK and Grove in the US. Ideally, I seek to have three channels open: an edgy New York imprint, one of the strong small presses (such as Lazy Fascist in Portland, who are doing some very exciting things), and then my own imprint for special projects that don’t fall into a clear commercial frame, or which have a strong multimedia component.

In my view, the key issues for aspiring writers to consider are these: Has the book been acquired by a passionate editor who has both some traction in-house and stability? What is the publisher’s vision and understanding of the emerging electronic world–are they leading it or being led by it? Finally, what is their international reach, or how is the contract written regarding foreign rights? My first book ZANESVILLE has become a cult hit in Russia and Poland. My book PRIVATE MIDNIGHT did very well in France and Italy. We have to think globally as writers.

What has been most successful for you when it comes to gaining visibility?

Public performance. If you’re not good at it naturally, you have to put in the time to get there. If you are good naturally, you have to put in the time to get better.

What lessons have you learned in your experiences with publishing that have had the greatest impact?

- Stick to what you’re doing—don’t be petty or jealous. Try to speak positively of those writers / artists you do feel kinship with, rather than resenting those you don’t like, who may inevitably end up in the moment being more rewarded. (Remember Booth Tarkington etc.)

- Anyone of your tribe who succeeds is a victory for you.

- Remember what got you excited about reading and writing way back whenever. Stay true to that.

- Constantly revise your opinions and remain promiscuous in your thinking.

- There is no more publishing “industry” in an art form sense. Maxwell Perkins and Bennett are long gone. There are also no more tastemakers such as Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound, Allen Ginsberg and Gore Vidal. Like skydivers, we’re on our own. But still the rule endures—try very hard to land into the wind.

- Whenever a poor young single mother, living in a crap little town in North Carolina takes the trouble to ride a bus for an hour to go to the library to find your book—and then takes the time to write you about it—consider that. Did the New York Times review really matter as much?

What is your opinion of the current state of the publishing industry? Do new authors have more or less of a chance of publishing with a big-five house than they might have ten years ago?

There’s more mediocre and truly terrible writing than ever before. People in New York and London publishing are demoralized—and many young editors have no life experience outside of parent paid internships at all. It’s a shambles.

But that sort of excites me. Whiffs of cordite, Kerosene and compromised liver! I say to my students, culture is over, and now you’re free to write what really matters to you. But think of it as what matters to other people, as if around a 55-gallon drumfire under a ruined overpass. Let’s put those rotten stuffed animals and broken toys on sticks and dance around. I like the shadows they make. For those still desperate to be published by the big five, I would consider trying to get into Iowa, moving to Brooklyn after, and then drinking and sleeping around. Why meddle with a proven formula? If that doesn’t pan out, come join us around the fire.

Thank you, Kris.

Readers: If you enjoy this or any of the other 5 On interviews and have writer or reader friends you think might also enjoy them, please share! The series is just getting started and there’s a terrific list of interview subjects ahead.

Kristen Tsetsi is the author of the post-Roe v. Wade novel The Age of the Child, called “scathing social commentary” and “a novel for right now.” She is also the author of the novels The Year of Dan Palace and Pretty Much True (studied in Dr. Owen W. Gilman, Jr.’s The Hell of War Comes Home: Imaginative Texts from the Conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq). Kristen’s interview series at JaneFriedman.com offers behind-the-scenes insights into all things writing and publishing.